The empathy problem

Modern culture is overrun with sympathy, but misunderstands and lacks empathy.

Apparently it’s not okay to show empathy for people

Recently, pop star and billionaire Selena Gomez cried her eyes out (Figure 1). She found out that violent criminals, who had illegally entered the US, were being extradited to their country of origin to face judgement for their crimes. This is something that was proposed by Hillary Clinton and Barrack Obama, and is an incredibly popular policy amongst Americans on both sides of the ever-widening political aisle. Luckily, she remembered to hit the record button on her iPhone and uploaded an Instagram story of the candid and genuine moment. Surprisingly (to Selena at least), the public reaction to the video was not good. Even her most ardent fans could see through the thin veil of performance. The Whitehouse posted the reactions of mothers of victims who had been killed by such criminals for whom Selena was crying. Upon realising the backlash, she deleted the story and replaced it with a black screen and the words “Apparently it’s not okay to show empathy for people”.

Hmm… was she showing empathy? Or was she using the display of “empathy” to manipulate her fans into believing that she is a compassionate person, failing to realise that compassion for violent criminals isn’t that popular? I think it’s obvious to most readers that, whatever she was showing, it wasn’t empathy. The potential reward of being seen as “empathetic” was clearly worth the risk of any downside from this charade, from Selena’s point of view.

The desire to display “empathy” is toxically potent

Last year, I read an essay by Gurwinder Bhogal on how “empathy” can actually lead to sadism and cruelty. His argument, which I find compelling, is that it hyper-focuses one’s sense of justice onto a single entity, and this subtracts from the equal and objective application of justice onto anyone outside of that focus. Gurwinder demonstrates his point, that “empathy” blinds us from objective judgement, with the interesting case of the Menendez brothers, whose murderous actions are being revised and retold in recent popular culture by those who, falsely, wish to infantilise and victimise the brothers:

“The problem is, the brothers are not actually victims. They’re liars and murderers. And the only reason they now have widespread support is that culture and technology have turned empathy into an emotionally transmitted disease that debilitates thought. Put simply, stupidity has gone viral.”

It seems that displaying “empathy” is one of the most beneficial social signals one can deploy in 2025, particularly in online circles where words are cheap and action is unseen and irrelevant. Gurwinder makes a compelling case that, when people are front-loaded with “empathy”, they subsequently fail to exhibit rationality and objective judgement.

This makes perfect sense in term’s of Jonathan Haidt’s “elephant and rider” model of moral judgement. When the elephant (emotional response) tilts its head in one direction, the course is set for both rider and elephant. The rider (rational response) can then do little to redirect the mighty elephant, and so will instead use its reasoning powers to reframe the directional decision in order to agree with the elephant retroactively. A powerful initial emotional reaction leads to motivated reasoning. Gurwinder’s point, with which I agree, is that, out of a keenness to display “empathy”, objectivity goes out the window, and reason and rationality are used to cleverly justify false judgement. Selena probably found herself in this predicament, explaining how she was able to rationalise such a ridiculous stunt in her own mind.

The desire to display “empathy” is so ingrained by modern society, with its unnaturally swollen social networks, that it is almost subconscious. Gomez and Menendez are two examples, but there are many such cases of misfired “empathy”. I would argue that some vegans motivated by animal rights are exhibiting a mild form of this (this topic deserves its own essay). Certain trans activists, whose recommendations for trans healthcare are completely contrary to the medical evidence, are guilty here too. Even certain activists for the cause of Palestinian human rights, which most would not only agree with but rally behind, find their emotions misdirected away from Palestinian wellbeing and towards support for terror or the destruction of others’ human rights. It is no surprise that this phenomenon is overrepresented within large social justice causes, where network effects increase the social/emotional/psychological reward on offer. It is a perfect blend of toxic compassion or pathological altruism, plus a social media age that rewards displays of “empathy” so highly, plus a distorted neo-Marxist worldview which allocates compassion based on surface-level group identities, rather than actual injustices.

But this essay isn’t an argument against neo-Marxism or identity politics. The eagle-eyed among you will have noticed my excessive use of quotation marks surrounding the word “empathy”. My problem with all of this, and with the people who are susceptible to the phenomenon hitherto described, is that empathy - actual empathy - is hugely lacking. It is sympathy that our modern world is flooded with, not empathy. In fact, many social issues would benefit from a reclamation and championing of real empathy.

The sympathy-empathy conflation

Selena was not overcome with empathy when she posted her video. She worked herself up to feel sympathy for imagined blameless victims of evil deportations. Likewise, my gripe with Bhogal’s essay is the presupposition that Menendez sympathisers are actually being empathetic. They are being sympathetic. The problem is that empathy and sympathy are too frequently erroneously conflated. Per the Cambridge dictionary, sympathy is “an expression of understanding and care for someone else's suffering”. Meanwhile, empathy is “the ability to share someone else's feelings or experiences by imagining what it would be like to be in that person's situation”.

This sharing of emotional experience occurs within one’s mind and aims to achieve deep understanding of the emotions and behaviours of others. Sympathy circumvents this understanding and simply phenocopies the emotional displays of others whilst psychologically coddling them. A sympathetic person feels sad when they see someone crying, or even apologises for it (“I’m so sorry that you’re upset”). An empathetic person figures out why they are crying and understands it at a deep level. There is no requirement for the empath to feel sad. The empath is free to rationally respond in any way they have reason to (Figure 2). Since true cognitive empathy is not associated with an outward display at all (it is a completely internal process), most real-world applications of empathy combine it with sympathy, because sympathy is an effective way to convey your empathy to others. This frequent combination of two different phenomena produces the semantic distortion.

Thus, sympathy is a basal emotional response that does not require much cognitive capacity. Whereas empathy is actually an incredibly difficult skill, and one for which I think many people overestimate their own ability. Adam Smith sets this out pretty clearly in his piercingly perceptive work “The Theory of Moral Sentiments”, which paved the way for his more famous economical insights. Of course, Smith never used the word “empathy”, since the term was an invention of the last century (Figure 3).

Few people make the distinction between sympathy and empathy accurately, including many psychologists. Yet there are some who have maintained the important separation between “a cognitive, intellectual reaction on the one hand (an ability simply to understand the other person's perspective), and a more visceral, emotional reaction on the other”.

Interestingly, the meaning of the word “empathy” in practice has morphed frequently over its short history, including to this day. This is frustrating to me. We need the linguistic tools to distinguish between the cognisance of others’ emotions and the emotional response that produces pity. If you find my definitions challenging, perhaps, feel free to henceforward substitute “empathy” and “sympathy” with “cognitive empathy” and “emotional empathy”. I empathise with your position here.

Sympathy is stupid

To understand why we are overrun with sympathy, we must recognise both its utility and its pitfalls. Sympathy is both powerful and easily tricked. The evolution of the phenomenon of “cuteness” clearly demonstrates both of these aspects. Humans recognise the features of babies’ faces - referred to by Lorenz as “kindchenschema” - and innately respond in a nurturing manner. This behavioural effect evolved to promote caregiving for infants and aid their survival to independence and adulthood1. This sympathy for cute things is a powerful evolutionary drive that was and is very important for our species. Yet this same effect is hijacked in our brains for animals which happen to share certain facial features of human babies, such as large eyes and round faces. In this way, a deep-rooted neural mechanism originally evolved to promote human infant survival has led to the existence of dachshunds and Moo Deng.

The same principles of evolutionary psychology apply to all expressions of sympathy, not just cuteness. Sympathy evolved as a powerful rudder to steer human behaviour towards caregiving for those within one’s own gene pool. Yet it can be readily hijacked by any pirate who happens to board the ship, in which case its use becomes maladaptive.

Emotional support for the Menendez brothers is a sympathetic response, driven by cues that cause people to perceive them as victims in need of caregiving. The fooling of the sympathetic response was even relied upon and exploited by the Menendez’s lawyers, as noted by Boghal:

“Abramson and Lansing tried to portray the brothers as sweet and naïve kids. They dressed them in boyish clothes like school-style sweaters. Lansing kept referring to them in court as “the children”, and Abramson would often maternally place her arm round Erik, and pick lint off his sweater. Her behavio[u]r was so conspicuous the judge reprimanded her for it.”

Similarly, Selena Gomez let the cloudiness of sympathy fool her better judgement. She may have imagined children being ripped from their loving parents’ arms - a mental scene certain to evoke emotion - and found that it upset her, because those imaginary children and parents are sad so she is sad.

This fallibility of sympathy is part of the reason why it is so widespread. Since sympathy is such a stupid (i.e. does not require cognition) emotional response, it can be applied to a far greater diversity of things than empathy can. Empathy, on the other hand, has a far more restricted applicability, being fundamentally limited by intelligence.

Sympathy is promiscuous

The relative promiscuity of sympathy and the limitations of empathy are easily observed. As with cuteness, we are perfectly capable of feeling sympathy for animals. One could even argue that this cross-species sympathy is adaptive, since we would want to be motivated to care for animals on whom we depend, even if just for emotional support (e.g., a pet dog). Yet there are plenty of instances of completely maladaptive sympathy for animals, including excessively sympathetic reactions to nature documentaries2. Nature documentaries are an interesting example since they showcase the deliberate abuse of sympathy: The likes of David Attenborough absolutely play up to the misplaced sympathy of the viewer by personifying and anthropomorphising the animals because it is a guaranteed way to increase viewer engagement. I will come on to the reasons why actual (cognitive) empathy for animals is an impossibility later, but for now let’s explore the full spectrum of the promiscuity of sympathy.

Last year, my local Co-op employed a squadron of six-wheeled robots to deliver groceries to houses in the vicinity of the store. These robots would frequently get stuck at pedestrian crossings, unable to make the risky crossing without human guidance. Cycling past these fellas, I would feel a tug on my heartstrings. How cute—the poor little guys just need a little bit of help! Now clearly, this isn’t empathy, because the emotional state of a robot on wheels is definitively non-existent. Yet, sympathy swelled in me nonetheless, and I immediately jumped to anthropomorphise the clanker. My reaction was not unusual though - as discussions with friends and colleagues confirmed. In fact, the manufacturers were so confident in the ability of the robots to invoke sympathy that they programmed it to say “thank you” when a human helped them out of a sticky situation.

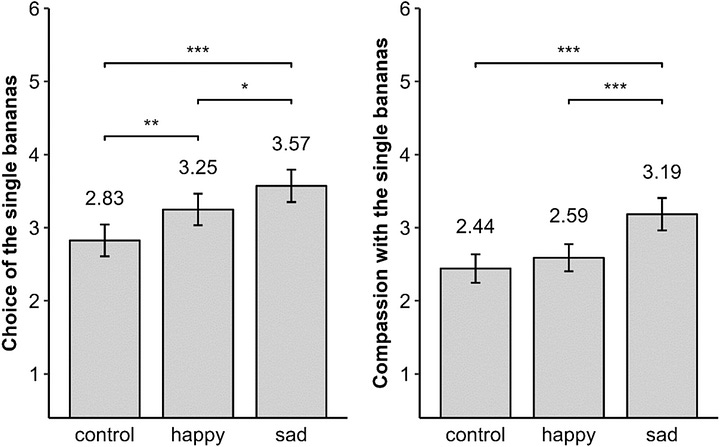

Sympathy is such a broadly applicable and powerful motivator of human behaviour that it can even be applied to completely inanimate objects (I’m excluding robots from this category since they are “animated” in the sense that they move and interact with humans). Marketing teams long-ago realised that anthropomorphising their products increases sales. This has very successfully applied to food items with a view of reducing waste. In a recent study, the relative power of sympathy-inducing versus happiness-inducing signage for the sale of leftover single bananas was directly tested. The researchers found that labelling single bananas as “unhappy” bananas that had nothing wrong with them and just wanted to be sold to a good home was by far the most effective strategy for increasing sales (Figure 4).

Promiscuous sympathy and the commercial leverage of promiscuous sympathy form a positive feedback loop. This leads to a sort of sympathy-creep where the Overton window for sympathy stretches ever-wider. The remarkable ability to anthropomorphise and sympathise with just about anything is fascinating, but promiscuous sympathy and its societal exploitation is something people ought to be cognisant of when trying to navigate the world rationally.

Empathy is rare and limited

In stark contrast to sympathy, empathy is actually an incredibly difficult thing to express. It also seems to be an intelligence-adjacent innate ability, rather than a learnable skill. Much like intelligence, empathy is also an ability that I see people overestimate their own aptitude for. The “me, an empath” meme, a Covid-era classic, satirises this tendency for people to claim a high capacity for empathy and to conflate sympathy and empathy (Figure 5). Being packaged within intelligence (“emotional intelligence” is just intelligence in a specific dimension, not separate to intelligence), high levels of empathy are only present at the upper tail of the Gaussian distribution of human intelligence. Thus, it cannot be as reliably abused by commercial interests; there is no commercial motivation to exploit or stretch human empathy as there is for sympathy.

Even those with a high capacity for empathy will struggle to apply it as broadly as they can sympathy. I have already stated that empathy for a robot is impossible—I hope this point is trivially obvious to the reader. For the same reasons, empathy for animals is also impossible, as alluded to earlier.

Empathy requires knowledge and understanding of the emotional state of the object of the empathy. We simply have no idea if animals actually experience emotional states in the same way that humans do. All we know is that animals respond behaviourally to certain cues in similar ways that humans would in analogous situations, and that our human responses in these instances are driven, in part, by emotions. However, anyone claiming that animals experience emotions like humans do are falling foul of a big fat case of the correlation-causation fallacy. The assumption that a conscious emotional experience is necessary to cause behaviours that we perceive as being emotionally driven has zero evidence.

In attempt to overcome the empathy blockade that is encountered as we move from humans to non-humans, we anthropomorphise animals. It is easier to imagine that an animal is a human than for a human to imagine being an animal. If you have ever stepped on your pet dog’s paw by accident, you’ll notice a few things:

The dog yelps/recoils

You think about how painful it must have been

You feel awful

The “must have been” here is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

Let’s break this down a bit. When the dog yelps, we immediately think of what it would take for us to let out such a yelp. We think of times that we have experienced pain, recall our reactions, subconsciously plot the relationship between emotional experience and behavioural response, position the dog’s response on that graph, and interpolate the missing value of “amount of felt pain” experienced by the dog (Figure 6). But the dog’s experience of pain does not belong on this graph. A dog would not have access to the x-axis at all. Perhaps it could have an orthogonal z-axis, but there are no datapoints in that dimension with which to perform any interpolation (perhaps a few decades more of consciousness research might provide these data).

For a human, the x-axis is the input and the y-axis the output. Yet when we sympathise with animals in pain, we use the y-axis as the input and attempt to infer cause from correlation. This is logically fallacious.

To understand your own capacity to project the human emotional experience of pain onto things that definitively lack human emotional experience, perhaps watch this video of a Twitch streamer physically abusing his android robot and ask yourself how it makes you feel.3

Just as we know that a robot does not experience pain, we also know that dogs (and other animals) do not experience human-level consciousness and therefore do not experience pain as we do (since it is a conscious experience). This is not to say that animals do not experience pain at all. They certainly do, since it is a highly successful mechanism for self-preservation that evolved a long time ago (preceding chordata even). My point is that most of the awfulness we feel for animals in pain is due to us imprinting the human experience onto the behaviour of the animals. If you want to argue with me that the richness of consciousness of a dog is on-par with that of humans, ask yourself how happy you would be to live the life of the average dog.

Okay so empathy, unlike sympathy, seems to be restricted from inanimate objects, abiotic animate objects, and non-human animals. But surely it can at least be applied to all humans? Not so fast…

One of the reasons racism exists as a phenomenon is because humans do not cognitively empathise with humans that are sufficiently different to themselves. I used to think that this was a deliberate refusal to empathise, for self-serving reasons. But I am coming to realise that this may simply be a skill issue, and most humans are cognitively incapable of empathising across the full spectrum of human diversity. The close correlation between intelligence and tolerance of others certainly corroborates this notion.

I previously thought that education was able to overcome this empathy gap between humans of divergent ancestries/experiences, but I may have been wrong. I had a conversation about empathy last summer with a left-leaning friend who has a Masters in a humanities subject from a top UK university. I had already laid out my distinction between sympathy and empathy when I asked her whether she was able to empathise with a black person. I was surprised to hear her admit that no, she could not. When I probed deeper, she explained that the lived experience of a black person is unique and unfathomable to a white person, and therefore she cannot hope to truly empathise with one. I was dumb-stricken. I insisted that the point of empathy was to imagine the lived experiences of others and thereby understand them. She reiterated her rule. It seems that the radical fringe of leftwing academia has come full-circle and re-rationalised the race-empathy-gap by defining the lived experiences of different races as sacred and unknowable (from the perspective of a white person at least - I don’t suppose this rule is bidirectional). Importantly, my friend is right. I think she is incapable of empathising across such a gap of “lived experience”. Like most of us, it is unlikely that she has the elite cognitive capability to truly cognitively empathise across a broad spectrum.

This is not to call my friend racist. Compensatory sympathy may be responsible for some of the social progress we have seen regarding unjust discrimination, and my friend is certainly a sympathetic person. What western society has achieved is an elimination of race-based (and other types of) prejudice in spite of extant and pervasive empathy chasms. Race is an unremarkable human trait within this phenomenon—most people would struggle to empathise across a multitude of other categorisations, including class, education level, sexuality, sex, health status, political ideology, and even intelligence level.

If you think you are especially empathetic, try the following: if you are straight, try to imagine what it is like to be gay (if you are gay, do the inverse). I mean genuinely mentally adopt that alternate reality. You know how people of the opposite sexuality behave, and how they they say they feel, and you could probably describe these observations in conversation—there is no insufficiency of data here. And yet it is an outrageously difficult task to actually imagine being sexually attracted to something you probably find a bit gross.

The thing is, most humans don’t even understand their own emotional experiences. So the expectation of being able to perceive, imagine, and understand the emotional experiences of other humans is a ridiculously ambitious one. Subsequently, we should all follow the example of my socialist friend, and make a habit of humbly admitting to our own limited capacity for empathy more often (though perhaps citing this essay, rather than some mindless neo-Marxist maxim).

Empathy and sympathy can be inversely correlated

As with general intelligence, I frequently observe a powerful Dunning-Kruger-like effect when it comes to claimed versus actual capacity for empathy. Over-indexing on sympathy seems to be the modus operandi for those on the empathy-equivalent of the Dunning-Kruger “peak of Mount Stupid”. This contributes to an inversion of the positive correlation one might expect between sympathy and empathy.

Evidence for this inversion can be seen when comparing conservatives and liberals trying to empathise with each other. Interestingly, the empathy gap between political ideologies is not evenly bidirectional. When tested for their ability to respond to various moral questions as if they were someone with the opposing political view (a task that requires true cognitive empathy), liberals were much less empathetic than conservatives, with the most liberal-identifying people performing the worst (Figure 7).

This is in stark contrast to self-reported “moral allocation”, or sympathy, where liberals cast a far wider net, finding humans and non-humans to have equal moral worth, for example (Figure 8).

A less politically provocative demonstration of this inverse correlation would be to consider how various people react when someone dies. When offering condolences to another person for their loss of a loved one, the phrase “I can’t imagine what you are going through” is frequently used. This commonplace phrase actually juxtaposes empathy and sympathy very well. You are offering all of the sympathy and compassion in the world to them, yet you do not understand their emotions at all, and you admit as much.

Conversely, if you are capable of exhibiting greater empathy, you might, paradoxically, offer less sympathy. If two siblings are both grieving the loss of their shared parent, their capacity for empathy for each other is about as high as is conceivable for any situation (the gap of lived experience is minimal). Yet an empathetic sibling might actually express less sympathy than a work colleague, say, if they deem their sibling’s grief-response to be self-destructive. If, for example, one sibling is wallowing in self-pity, disregarding personal hygiene, not showing up to work etc., the sympathy of a colleague might increase this negative behaviour by directly affirming it (“take all the time you need before coming back to the office, you must be having a really tough time—I can’t imagine how I’d react if my parent died!”). An empathetic sibling, who has gone through the same experience, but reacted less pathologically, may decide not to overly-coddle their sibling with sympathy. It is because of their increased empathy that they are able to rationally decide to withhold sympathy for the good of their sibling.

Importantly, actual shared experience here is not necessarily required to understand another’s emotions—that is literally the point of empathy. A good therapist, with a high capacity for empathy, would more closely mimic the response of the empathetic sibling than the sympathetic colleague (referring back to Figure 2). This requires a certain level of intelligence (innate trait) that not all possess, in addition to knowledge of effective therapy strategies (learned skill).

Empathy is the solution to the sympathy problem

Empathy frees you from a knee-jerk sympathetic response, since it provides the knowledge and understanding of another person’s emotions necessary to make an independent evaluation of their situation and respond in the best way. Responding in the best way here means the maximally compassionate response in the long-term, whilst low-empathy and high-sympathy responses aim for local maxima of compassion instead (short-term benefit; long-term detriment). Ironically, this maximally sympathetic response primarily serves the provider of sympathy rather than the recipient, since it feels good to offer sympathy and others view you as being kind (which you are in that particular moment, but not in the long-run).

It is perhaps worth noting that empathy and sympathy are often combined and positively correlated. Sympathy does have utility in comforting a suffering person—in moderation. Any egregious over-indexing on sympathy, however, raises red flags since it indicates compensation for low cognitive empathy, in addition to the narcissistic tendency to be perceived as compassionate (à la Selena Gomez).

The wisdom to balance sympathy with empathy lies in the appreciation of Adlerian psychology over Freudian psychology, with the latter being stubbornly pervasive in modern popular culture despite it being a completely false paradigm by 21st Century standards. If empathy is learnable, Adler is where I would start.

In addition to an increase in acknowledgement of our limited empathy, we would do well to resist the tugging urge to display compassion and sympathy as much as possible, particularly in our age of social media. Introspection as to whom is most benefiting from the display of sympathy can help us to realise that, whilst it always benefits us to display sympathy, it is not always the best way to alleviate the suffering of others in the long-term. A societal reverence for and focus on cognitive empathy, as well as understanding of the nature of sympathy, would undoubtedly create a better world.

I dislike teleological descriptions of evolution, since they imply some sort of agent rationally driving evolution in one way or another. It is a necessary practice for brevity, but in this footnote I am under no such obligations! Substitute in the following if you, like me, want to be an absolute stickler for the precision of language:

"The gene variants that happened to encourage this kind of behaviour in response to cuteness were able to propagate through generations at an increased frequency compared to alternative variants within the gene pool because the offspring containing the Kindchenschema-response gene variants were more likely to survive through to reproductive age and themselves pass on genes (because of the added protection and survival benefit created by the behaviour)."

Notice the misuse of the term “empathy” in this article.

There are actually two responses this video might conjure for you. One directed at the robot: sympathy (maladaptive). The other directed at the humans: disgust or even hate (adaptive). The disgust response is appropriate, because we recognise that the actions of the human, even though they aren’t harming anybody, violate some sort of moral code. That moral code is the sanctity/degradation moral pillar, and thus the video is likely to generate a stronger response amongst more conservative-leaning people, since this pillar is comparatively absent for liberals (who emphasise the car/harm pillar instead).

I agree. Though I think the gap between the two is artificially widened by social media. Empathy, as your DALL-E image aptly shows, cannot be noticed externally unless the empathetic subject expresses his understanding or acts upon it. On the other hand, sympathy is readily and easily on display, as you and Selena Gomez have taught us. This difference becomes nearly hyperbolic in the context of social media, where attention spans (on most platforms) are ever shorter. Tik tok and Instagram particularly are built off of sympathetic interactions and likes, whilst longer form mediums which give the necessary space for people to elucidate their cognitive empathy are neglected. This could suggest an underrepresentation of empathetic ability (obviously of many other easily imaginable traits as well) online.

"Empathy" is the narcissist's version of compassion; but with a lot less actual concern for others and a lot more conspicuous virtual signaling.

Leftism attempted to weaponize empathy, and the result was that leftism destroyed empathy - just like everything else the nasty religion touches.