If you’ve been paying attention to the news recently, you might have seen reports that Trump is waging war. B-2s may have decimated the Iranian nuclear physics programme, but the real war on science is occurring domestically, we are told. Last month’s attempt by the Trump administration to strip Harvard of the ability to sponsor foreign exchange visas is the latest showing on one of the battlegrounds of this war. As a postdoc on a J1 visa myself, I can absolutely empathise with those at Harvard in the firing line. Many faced the choice of either finding another US institution to sponsor them, or to go back to their country of origin.

Trump’s war was declared almost immediately upon his inauguration. It started with a proposed slashing of “indirect costs" rates for National Institutes of Health grants to 15% back in February. This has been recently copied by the National Science Foundation. Harvard has also had its tax-exempt status threatened by Trump himself and billions in funding frozen. The attack on universities isn’t just directed at Harvard, with Columbia University also seeing federal research grants slashed. More broadly, we are told that the NIH itself is “under siege”.

At the same time, Chinese science seems to be stronger than ever. The CCP has formed a secretive Central Science & Technology Commission, swanky new research institutes seem to be popping up all the time there, and the argument can be made that China is now the global scientific superpower in certain fields. Was the David versus Goliath story that we were told about DeepSeek and OpenAI just a foreshadowing of a much grander global shift in scientific hegemony?

I moved to the US to start a postdoc just before Trump took office this year. With the apparent seismic shifts in the scientific landscape, should I be thinking of getting the hell out of here? Should I just go back to Cambridge with my tail between my legs? What about doing some Naturwissenshaften at an MPI in Germany? Or maybe I should abandon the occident altogether and accept the generous CCP relocation package in a shiny new Chinese lab? When I sit back and think about where I would choose to apply for postdoc opportunities if I was finishing my PhD only now, I have to admit that there is only one clear answer: the US of A.

Media headlines telling of the destruction of science are often pre-emptively doomerist, lack key context, or blatantly over-exaggerate the reality of the situation. Here I outline why US science is strong and not really under any kind of existential threat. I make the argument that the US is the best place in the world to do science. Trump isn’t, can’t, and won’t change that, and you should be weary of the incentives behind those telling you otherwise.

Culture > politics

Before I parse fact from fiction regarding the alleged death of US science, I first wish to make a broad foundational point: In a democracy, culture is upstream of politics. The only reason the Trump admin is cutting anything related to science or academia is because that’s what people voted for. There has been growing distrust in institutions, and the institution of Science™ has become politicised, corrupt, and untrustworthy. Peer-review is pretty broken, there is a reproducibility crisis, and the big journals have basically become propaganda outlets for the Democrat party. The goal of dispassionate pursuit of truth in US science has been slowly diluted for decades. Even with these maladies, US science has remained dominant. An attempt to reinvigorate and realign US science shouldn’t be mistaken for an attempt to kill it.

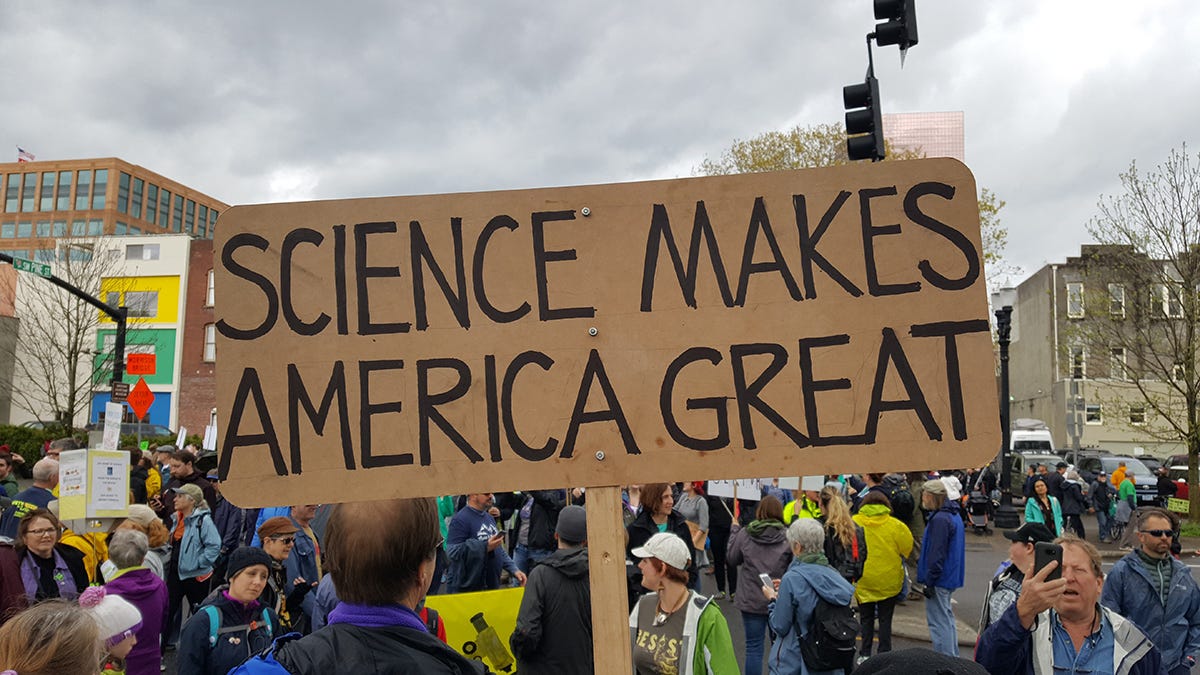

Leftists might be upset that democracy is swinging against them right now, but it is within the very nature of US democracy that, should public opinion of scientific institutions improve in the future, politicians will fulfil the desire of the δῆμος and inflate the NIH/NSF budget once again. The US, with its unfettered free speech, tolerance for peaceful protest, and separated branches of government, is arguably the strongest and most stable democracy in the world. If you want policies that favour science, then first convince the voting populace — in democracies, politicians are followers, not leaders. I would encourage my fellow scientists to direct their anger not at the politicians who are simply acting on behalf of the will of the majority, but towards the institutions that have destroyed public trust in science. This is the root cause of the issue. Trump’s heavy hand is merely a symptom.

Whilst the public reverence for Science™ has decayed, the cultural adoration of American exceptionalism is stronger than ever. Aspiration, meritocracy, and the pursuit of success and excellence are so deeply ingrained in the American psyche that no politician, not even Trump, would dare to threaten that perception. Most Americans care deeply about winning, and winning at science is included in that.

The American left is now full of institutional conservatives sticking up for old establishments like Harvard, whilst MAGA has taken the tech right under its wing. The result is the presence of sizeable factions within both party coalitions that prioritise scientific progress and the funding it requires, meaning pro-science is one stance that has bipartisan support. With this cultural backdrop, it seems unwise to bet against US science.

Signal from noise

It is easy to paint a picture, as I have done in the introduction, of an evisceration of science by the Trump admin. It is less easy to analyse the reality of the situation dispassionately, rationally, and without slipping into attention-grabbing negativity bias.

To level the playing field set up by much of the news media, let me play Devil’s advocate for each of the various “attacks on science” we have been told are unfolding. By reading on, hopefully you can understand each side before forming your own opinion.

Indirect costs cap. If a scientist wins an NIH grant for, say, $1M, the NIH also forks over an additional amount to the scientist’s institution itself in order to cover administration and overhead costs. The percentage of the original grant that must be given is individually negotiated by different institutions, meaning places like the Salk Institute (where I work) get $900k extra, whilst University of Florida get just over $500k.

The secret is, a silent plurality of scientists were actually quite excited at the prospect of the 15% cap. This would mean more grant money is given directly to us scientists, since the total funds are fixed — decided by the Congress, not the White House. Most key core facilities are in fact funded by direct costs, via hourly charges to our grants, meaning most of the cutting would indeed hit wasteful spending and administration. I personally would happily trade better chances of an extra NCI grant to fund some of our lab’s work on liver cancer, for example, in lieu of more indirect funds to go towards the monthly “Salkfest” events at my institute, where taxpayer money gets spent on free food and festivities during work hours (don’t get me wrong, I get free lunch whenever it’s available, but I can see why a regular taxpayer might not want to fund it).

Regardless of anyone’s stance on this particular matter, in line with my point about the stability of US democracy, both NIH and NSF proposed caps have been blocked by district judges pending further litigation, and US science remains untouched.

Visa sponsorship removal. The visa situation at Harvard followed ongoing negotiations for records of students involved in illegal activities during campus protests. Harvard argues that revealing these records would exceed what is legally allowed, whilst the Trump administration argues that Harvard is not complying with reasonable requests. The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle, as always, and time will tell as the court case plays out.

It is undeniably true that foreign students and postdocs here are simply collateral damage, and this is blatantly unfair. It was nonetheless interesting to me to observe an outpouring on X of offers from lab heads at other institutions to take on these students. Clearly the understanding was that the issue is with Harvard, and not with US science as a whole. It seems likely to me that students potentially scorned by this move would desire first and foremost to relocate within the US, rather than going back home.

Needless to say, here too a federal judge issued an indefinite restraining order to block the order and foreign students and postdocs will not have to move anywhere whilst the court case ensues. US science remains untouched.

Removal of tax-exempt status. The visa issue is the least of Harvard’s worries. It has also had its tax-exempt status threatened, as a means to force them to comply with civil rights laws, which they were violating via their hiring and admittance practices. Let me repeat that point, because this key context seems to be missing from most media articles covering legal battles between the federal government and places like Harvard: multiple prestigious universities in the US were found to be illegally hiring and admitting based on race, the Supreme Court directly ruled that they were breaking Civil Rights laws, and the universities have carried on nonetheless. The judicial branch have tried, is it not the role of the executive branch now to see what it can do?

Regardless of the motivations for Trump’s actions, Americans may see this tax-exemption change as an outrageous government intervention on a private non-profit educational institution. Interestingly, Brits certainly didn’t seem to think so when the UK’s Labour government implemented this very same change against all private primary and secondary schools last year with very little public resistance (in fact, the move was largely praised because people in the UK see it as immoral to be able to pay for a better education for your kids). Unlike schools in the UK, who are silently adapting to the change, including by raising the school fees such that the schools become even more financially exclusive than before Labour’s move, Harvard hasn’t had to do anything, since the threat was just a mean tweet (or Truth to be precise) — one that made headlines, of course. Tweets, though, don’t constitute a “war on science”, and US science remains untouched.

Cutting of scientific funding to specific institutions. Harvard and Columbia University, both hotbeds of anti-American and anti-Jewish cultural rot last year, were also hit hard by aggressive cutting of research funds directly. Because of the grants system I outlined in point 1, scientists’ grants represent a major source of funds for the universities. This means that, to punish the university administrations, the Trump admin must go through scientists. In this way, scientists are collateral damage in a war between the overpaid bureaucrats who (fail to) run the universities and a frustrated government who can’t seem to pull any levers without being kneecapped by district judges (which pushes the executive branch to reach for larger and larger levers).

Even if Trump was well-intentioned to target the universities themselves, he is doing so via punishing scientists. This is clearly wrong and ineffective, right? We all know that universities, even though they have very large endowments and charge exorbitant fees to students (which is quasi-government funding when you consider forgivable student loans), can’t just spend these funds willy nilly. The endowments can only be appropriated for specific predetermined things. I certainly believed this dogma until I brought myself up to speed with how Columbia are dealing with the cuts. Writing to their research community on March 31st, the senior leadership assured:

Centrally, we committed to fund those individuals whose salaries and stipends were previously funded with federal support on now-terminated awards, using institutional funds, while we undertake the review.

Clearly, there are funds to spare and the University can buffer the loss of government funding. On May 6th, Columbia announced that they had reached the end of their review process and were sadly letting go of “about 20% of the individuals who are funded in some manner by the terminated grants”. They also outlined that graduate students and postdocs on terminated grants will all be supported for another year by the university, meaning that the 20% is likely junior research staff or admin staff. Either way, for them to be able to fund 80% in perpetuity is a great outcome and demonstrates the ability of the universities to utilise their own money instead of the taxpayers’. Columbia have also now set up a “Research Stabilization Fund” to aid researchers who are in the throws of uncertain grant applications/terminations.

How is Columbia able to cough up so much money all of a sudden? In addition to the short-term endowment spending, they are making longterm room in the budget by reducing administration workforce and costs:

We will continue to make prudent budget decisions that will ensure long-term financial stability across the University, including making significant budget reductions within the University’s central administration. Across the University, we have set parameters to keep most salaries at their current level, without increases for the next fiscal year, with some schools and units providing a modest pool for employees at the lower end of their salary distribution. We have also developed programs to further streamline our workforce through attrition and are preparing to launch a voluntary retirement incentive program, the details of which will be shared next week.

In other words, they are cutting wasteful bureaucracy, capping the salaries of overpaid admin staff, and incentivising retirement to remove gerontocracy. This is exactly what Trump, and many of his voters, desired. So perhaps his actions directed initially at scientists were well-advised? Rather than killing science, an argument can be made that a rejuvenation and streamlining of Columbia, a scientific powerhouse, will be good for US science in the long run.

Cutting of scientific funding for specific areas of research. There have been claims of grant funding being cut or applications rejected due to the presence of specific “woke” terminology in the abstracts or titles of federal grant applications. While many claims, particularly on social media, may just be perceived sleights — used as an excuse for a crappy proposal — there does seem to be a legitimate attempt by the new NIH leadership to shift the focus of what they fund. You could argue this one either way. Either: obviously it’s up to NIH leadership to define what the NIH funds. Or: obviously the NIH shouldn’t be able to shape research objectives through a political lens. Luckily I don’t have to conclude this debate in my head, because earlier this week a federal judge ordered the immediate reinstating of many of these grants. The Trump admin can appeal the order, which could take it up to the Supreme Court. If they don’t, though, then this is another case of US science (even woke science) being untouched.

For every example here except the Columbia cuts (which, as I argued, might turn out to be net positive for science), judges have blocked Trump’s actions. I understand that Trump can be unpredictable and reactive. It’s also important to understand that media outlets, like Nature who dedicate entire collections to Trump’s perceived attack on science, thrive off the clicks and subscriptions that their fear-mongering generates. MAGAs are frustrated with “activist judges”, while TDS sufferers are chomping at the bit for the next headline of “Trump is killing science” to reassure them that their team is the good one. The reality is that American democracy is functioning as it was intended to, and US science is doing just fine.

Brain drain?

In 1933, having removed the power of the Reichstag, Hitler enacted the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which allowed the Nazis to fire any undesirables (Jews, communists etc) from the civil service. In the same year, the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars was formed in the US, which worked until 1945 to facilitate the immigration of primarily Jewish scientists persecuted by Nazi/fascist rule. The result was a brain drain from Europe, including giants such as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and Edward Teller. Many of these physicists would go on to join the Manhattan Project, the fruit of which would ultimately play a major role in winning the war via Japan’s surrender.

Earlier this month, the New York Times argued that we are on the precipice of experiencing the reverse of the German exodus, in the form of a Trump-fuelled US brain drain. The notion is corroborated by Nature, who asked their social media followers whether they are considering leaving the US. A whopping 75% of their (anonymous and unverified) respondents said yes, in what I pointed out was a textbook case of stated versus revealed preferences (consider the difference in agency required for waggling your thumbs a few times to stick it to the orange man, versus uprooting your entire life and moving countries).

The Nature publishing group offers a career-finding service. Using this service, they reported “that US scientists submitted 32% more applications for jobs abroad between January and March 2025 than during the same period in 2024”. Interestingly, they only give percentages, and not raw numbers, likely because embarrassingly few people use Nature’s job-finding service (I personally know of zero scientists who have ever used it). Also interestingly, they are too shy to give data from any other years, lest we spot the very likely trend of year-on-year increases in international job applications since COVID.

The key difference between Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jewish scientists and Trump’s funding upheaval is to do with what Richard Hanania calls Elite Human Capital. The total number of scientists that moved from Axis-run Europe to the US in the 1930s and 40s was somewhere around 300. The outsized impact on US science of this exodus was not due to their quantity, but to their quality. Put simply and harshly, scientists that find themselves outcompeted in a more restrictive funding environment in 2025 are not the cream of the crop of US science.

If anything, if uncompetitive researchers are ousted and muster the agency to make their way over to the 36-hour workweek safe haven of France, for example, US science might even be better off for it. I had a conversation recently with a smart young scientist working on a NASA-funded climate project attempting to clean up and analyse huge amounts of citizen-acquired data that is unusable in its current form. He told me how his department is expecting cuts, but he is unsure whether it will kill the entire project, which puts him out of a job (he’ll just get another one, he’s a data scientist), or if the cuts will mean getting rid of the most useless team members, the prospect of which he told me he was secretly very excited about. In this way, the looming “brain drain” may actually be a much needed brain cleanse.

To determine whether a brain drain of the actual top scientists might happen, we mustn’t concern ourselves with polling of the average scientist, but consider incentives for these top scientists. In their article, the New York Times interviewed some of such scientists, including Ardem Patapoutian, an immigrant scientist whose work on the pressure-sensing PIEZO channels in cells earned him the Nobel Prize in 2021. Ardem had posted criticism of the Trump admin regarding science funding on Leftist containment dome Bluesky and was almost instantly approached by the CCP with a relocation offer:

In late February, he posted on Bluesky that such cuts would damage biomedical research and prompt an exodus of talent from the United States. Within hours, he had an email from China, offering to move his lab to “any city, any university I want,” he said, with a guarantee of funding for the next 20 years.

Those outside of academia might not appreciate how unbelievably valuable this offer is. It would take something very extreme indeed to persuade an ambitious scientist against 20 years of guaranteed funding. Ardem’s response?

Dr. Patapoutian declined, because he loves his adopted country.

I rest my case.

China

China’s huge effort to try to grab American scientific talent can perhaps explain some of the media buzz around the death of American science. We know that China has been desperate to topple the US for decades. A bombshell report from last month detailed the vast extent of academic espionage that the CCP undertakes at US universities in attempt to sap knowledge and human capital from the global scientific leader. To think that CCP espionage is limited just to American universities, though, is naive.

New York Times reporter Vivian Wang recently published an extended advert for a new research institute in Hangzhou, China. Vivian notes on her NYT page that reporting on people living in China requires care, since “people can often be punished professionally or legally for criticizing the government”. Given Vivian has now lived in Beijing since 2021, we can take what she says about fantastic new Chinese universities with a pinch of salt.

Nature, too, recently published a very pro-China editorial, which focuses on China dominating the Nature Index top 10 — a measure of how many publications per institution are published in a selection of 145 top journals. This index doesn’t take into account the size of institutions (per capita, Harvard dominates the Chinese Academy of Sciences). It also doesn’t account for the fact that Chinese labs publish a lot of fraudulent science — publishing 17,541 retracted papers between 1996 and 2023, compared to USA’s 3,006. The incentives in China are to game the publication and peer review process, not to produce meaningful science — hence there being just a single Nobel Prize awarded for Chinese science.

Another eyebrow-raiser for me was the “Featured Jobs” section on Nature’s online service, which exclusively contain new postings in China. It may be the case that this is benign — just an algorithmic consequence of China having a great number of well-paid job openings and a dearth of talented scientists to fill them. Still, the terribly convenient alignment of CCP efforts and western media reporting narratives do start to smell slightly marine.

The CCP aren’t the only Machiavellians here though. Like the New York Times, NPR also tried to draw the Manhattan Project analogy, reporting that a number of European universities and politicians have launched efforts to poach US scientific talent. This includes Aix-Marseille Université in France, which has launched a “Safe Place for Science” programme dedicated to attracting and funding American emigrants “in particular those focusing on themes related to climate, the environment, health and the human and social sciences”. Climate science is a heavily politicised field rife with publication and funding bias. I’m not entirely convinced that the fifteen scientists due to fill the spots at Aix-Marseille Université will be particularly missed.

I’ve already alluded to how the media incentive to catastrophize about Trump is self-serving for them. Promulgating that “Trump is killing science” to predominantly Democrat-voting scientists and liberal elites, preying on our evolutionarily hardwired negativity bias, is a powerful way to grab attention, clicks, and subscriptions. The combination of domestic behavioural economics and foreign opportunism more than adequately explain what I would consider to be a large chasm between the reporting on US science and the reality of US science in 2025 so far.

The greenest grass

Ardem Patapoutian and I, despite our different propensities to catastrophize, seem to have reached the same conclusion regarding US science. Even granting that the bombastic criticisms of the Trump admin’s approach to science are true (which, as I have explained, they hardly are), it is worth underscoring why the US is still a superior place for scientists to work.

Based on the latest (2023) data, the US spends $823 billion per year on R&D. With PPP adjustment, the US’s $783.60B is trailed by China’s $723B. The vast majority of China’s funding is government-sourced, with corruption and low trust crippling their philanthropic efforts. Meanwhile, the US enjoys diversified funding with a very strong philanthropic scene. Since Trump’s inauguration, $820 million in grants have been terminated. This $820 million figure doesn’t constitute a real reduction in R&D spending though, since universities and philanthropic organisations are compensating for the Trump cuts. Such a kerfuffle about less than a 0.1% reduction in scientific spending feels a bit like 11-year-old Dudley Dursley complaining about only receiving 36 birthday presents compared to the 37 he was given for his 10th birthday. The fact of the matter is that the US is still the biggest scientific spender by a hefty margin, and this contributes to it being the best place on earth to do science.

Beyond funding opportunities, I believe the US is just a highly desirable place to live and work for driven individuals. In terms of work-life balance, USA represents the Golden Mean between the lazy Europeans and the browbeaten Chinese.

Ambitious scientists often find Europe a frustrating place to work — bogged down by excessive regulations and bureaucracy, and held back by pervasive tall poppy syndrome. Sam Rodriques, founder of computational biotech company FutureHouse, posted about his frustrations running a lab at The Francis Crick Institute, one of the UK’s premier research institutes:

… the primary challenge is cultural, and is both far less visible and far more pernicious. About 6 months in, I was sitting in a meeting with some other faculty and core facility leaders, arguing that we needed to build out an ambitious screening platform similar to those at the Broad. Heads bobbed up and down. And then, as people were filing out, one of the group leaders hung around behind and said, “Sam, you really have a lot of that American energy.” I chuckled. “Don’t worry,” she said, “Stay here for three years, and we’ll beat it out of you.”

Needless to say, the UK killed Sam’s desire to work in academia, and his new company seems to be flourishing in San Fransisco.

I have comparable experiences from my PhD at Cambridge. Most academic scientists, even some high-flying PIs, seemed to start work at around 10:30am. To be fair, they mostly pushed through until 6pm — as long as they’d had their late morning coffee break, extended lunch break, and mid-afternoon coffee break. Any attempt to break the mould there was frowned upon. About 3 years into my PhD, I recall setting up an old whiteboard by my desk to plan and brainstorm with. I wrote down every single remaining objective that I wanted to achieve by the end of my time there. This prompted one senior researcher to come over to my desk, chuckle at my list, and tell me that I should probably focus on just one project and that everything else on the list was too ambitious and unrealistic (she turned out to be incorrect).

At the opposite end of the spectrum is China, with its infamous 9-9-6 workweek. Science requires industriousness, sure, but it also requires creativity and ingenuity. Crushing the individual and removing any space for thoughts, dreams, and ideas harms scientific discovery. More than that, it makes China an unattractive place to work, evidenced by their extremely empty cities and labs. China can throw financial and scientific incentives out as much as they want, but they can’t overcome the fact that their country is a totalitarian sausage fest with a GDP per capita ~6.5x smaller than that of the US. As long as scientists don’t fall for Sinofuturist propaganda, I doubt China will be able to attract much US talent.

America, by comparison, is a rich, liberal, diverse nation that respects individual liberties and rewards individual merit. The US offers unparalleled opportunity — scientific or otherwise. Americans seem relatively unaware of the realness of the American Dream. Arnold Schwarzenegger paid homage to this on his recent appearance on The View:

I am so proud and happy that I was embraced by the American people like that. I mean, imagine, I came over here with the age of 21 with absolutely nothing. And then to create a career like that. I mean, in no other country in the world can you do that. Every single thing, if its my bodybuilding career, if its my acting career, becoming Governor, the beautiful family that I’ve created, all of this is because of America. And so this is why I’m so so happy to see first hand that this is the greatest country in the world and it is the land of opportunity.

It shouldn’t take monologues from immigrants like Arnold for Americans to realise how good they have it, nor should it take essays from immigrants like myself for American scientists to realise that US science won’t be killed anytime soon.

America’s scientists are awfully political. Nobody made them become so. Did they think they could afford luxury beliefs?

Shout out to you for following white supremacists on sub stack