This is part 2 of a 2-part essay on academic publishing. You can read part 1 here. If you like my ideas here, don’t shy away from liking and sharing this post. If you dislike my ideas here, I’d appreciate constructive criticism

TL;DR

Academic publishing is broken

Current “fixes” are partial or open new cans of worms

I propose integrating key features of non-profit open access journals, preprint servers, and social media platforms to create an optimised publishing system right here on Substack, which I dub Substack Scholar

I lay out a concrete plan of implementation

In part 1 of “Fixing academic publishing”, I laid out how a scientist might publish their results in an academic journal. Along the way I pointed out many pitfalls of the system. Boiling it down, here are the ten most pressing issues as I see it:

slowness

lack of motivation or reward for reviewers (with implications for “slowness” and review quality)

biased peer review stemming from the power of authors to suggest or reject certain reviewers

narrowness of scope of review leading to shallow or poor quality review. Given there are only 2-3 reviewers for most papers, it is unlikely that the editor will have actually found the best people to review a particular paper—especially in smaller journals)

politicisation and corruption of science via journal editors

increases in article length and incoherence in part due to input of reviewers

huge cost of publishing, typically funnelling taxpayer money or philanthropic donations to for-profit journals

lack of public access to the research

an inability to keep up with the pace and quantity of science

the misallocation of papers: bad papers can make it into big journals and be artificially elevated beyond their merit; good papers can be shunned into small journals where they go unread and unappreciated.

I also mentioned in part 1 that there have been some attempts to fix these issues. The problem is, all solutions thus far only solve a subset of issues, or introduce new issues at the same time as solving the original issues. Let’s take a quick look at them before I offer my own—perhaps we can glean something useful from these attempts.

Non-profit open access journals

One of the earliest attempts to offer life scientists new systems for publishing was PLOS (Public Library of Science). Harold Varmus (a Nobel Prize winner and previous NIH director), Patrick O. Brown, and Michael Eisen started the movement in 2000, later launching their first actual journal (PLOS Biology) in 2003. The organisation now runs fourteen different journals and has inspired a swathe of like-minded non-profit journals.

The PLOS model solves several issues with publishing. The main goal was to pioneer open access publishing, which they achieved. The organisation is a non-profit, meaning they are not motivated to erect paywalls wherever they can, and viewing the research in any of their journals is free to everyone.

Several PLOS journals also instruct reviewers to assess papers only on the basis of scientific validity, and not impact or importance. This improves speed and reduces publication bias. This move, though, introduces a new problem in that it now passes the buck to the readers, who will have to browse endlessly to find interesting articles.

Sadly, PLOS, being a big non-profit that employs a large staff, still has to charge fees in the thousands of dollars for publishing (even though there is no surcharge for open access since this is the default). Speed of publishing is still unideal, with PLOS One boasting a 43-day average time until first response and around 4-5 months for the whole process.

Most disqualifying, though, PLOS just doesn’t attract the best research articles. There is very little prestige to be gained by publishing here.

A hypothetical optimal publishing system would have open access to its research, like these non-profit journals, but it would have to offer more prestige to authors and reduce costs to zero.

Preprint servers

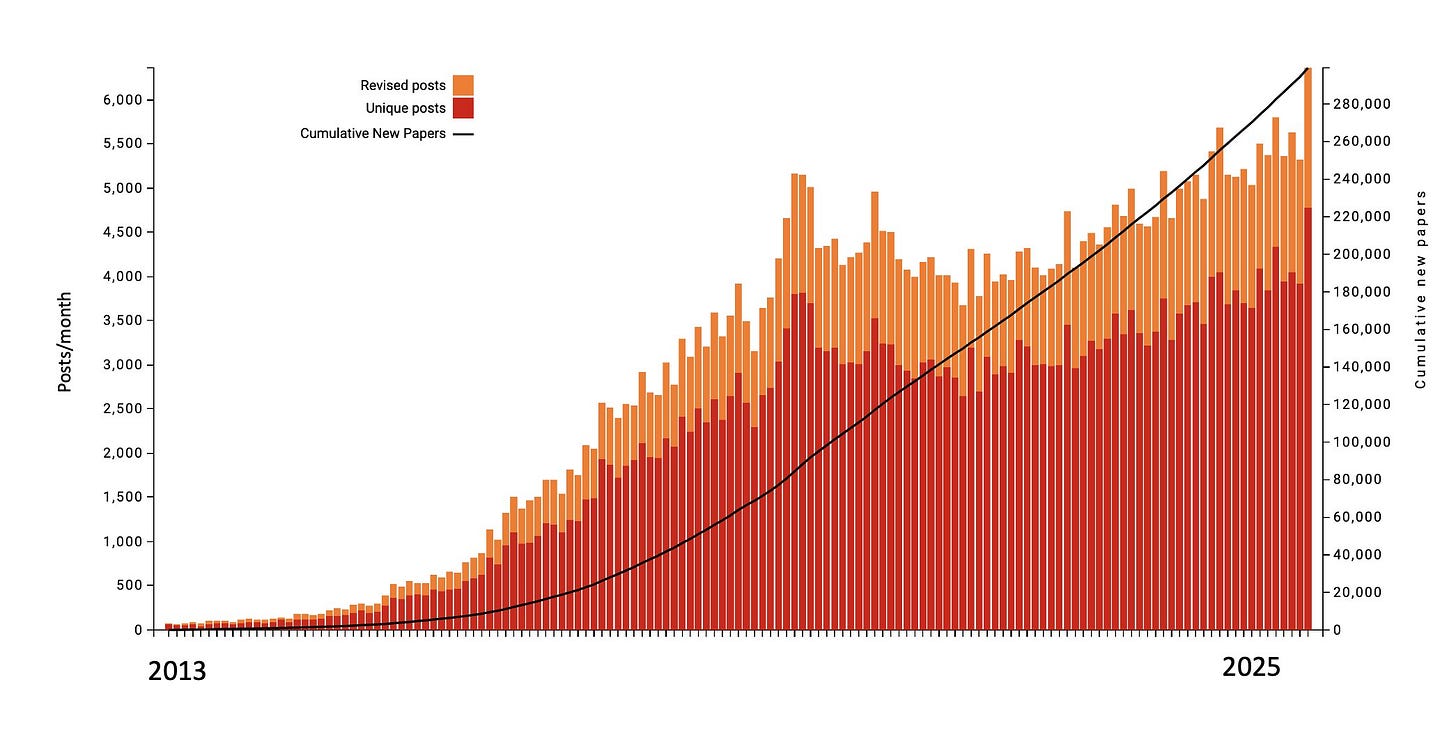

Preprint repositories are becoming increasingly popular these days. Arχiv, which was founded in the early 90s, is *the* hub for maths, physics, and computer science papers. More recently, bioRχiv (in 2013) and medRχiv (in 2019) were founded for biological and medical papers respectively.

The emergence of the preprint solves several issues in academic publishing. Most obviously, it speeds it up tremendously. Once you submit an article it is quickly vetted by a moderator and then uploaded, typically within 24 hours. The lack of formal peer review and powerful editors also removes publication bias and allows the public to see the paper exactly how the authors intended it to be.

For example, bioRχiv enabled Colossal Biosciences to publish a preprint exactly when they needed to in order to help defend their claim that their genetically modified wolves can be feasibly categorised as dire wolves during a media onslaught, as I wrote about earlier this year.

Crucially for computer science, these repositories handle *a lot* of volume, with arχiv now receiving more than 20,000 submissions per month. Indeed, the volume of research is all but crippling regular peer review in subfields like machine learning.1

While handling volume is a benefit of arχiv and its biological equivalents, enabled by the fact that they don’t do any peer review, this also means that there is no real quality control mechanism or method for finding the most interesting papers. The websites are labyrinths. Good, high-impact work from a small lab gets buried.

Crucially, while use of preprint servers is growing, they are not replacing regular publishing, but just adding to it. Most arχiv papers still seek peer review at a big conference or journal (the researchers need the boost to their CVs!). That Colossal Biosciences bioRχiv preprint that I mentioned is probably currently wallowing in the mire of peer review at Cell, Science, or Nature if I had to guess.

These preprint servers, like the open-access journals, have failed to overcome the prestige problem, and for that reason they don’t offer a complete alternative to traditional journals. A preprint is great for getting the work out there fast, but the job is not done until a big prestigious journal slaps their name on your work for a few thousand dollars.

A hypothetical optimal publishing system would be rapid, like preprint servers, but it would be the finish line, not a pit stop on the way to a prestigious journal.

Honourable mentions

We have now covered the two main alternatives (or supplements) to traditional academic publishing: preprint servers and non-profit journals. There are a couple other specific examples that deserve an honourable mention.

eLife

eLife, a non-profit biology journal founded in 2012, is currently trying a radical fusion of non-profit OA journals and preprint repositories which they call the “Reviewed Preprint” model.

In 2023, eLife announced that they would publish everything that they send for review as a preprint, and that they would then update the papers post-review, while keeping a version history. This is great for transparency, since you can see exactly how the paper was changed by peer review. Other than that, though, the model leaves much to be desired.

Editors still have ultimate power. In fact, they have enhanced power since they are the sole decision makers over initial publication of the preprint (they reject over 70% of papers that get submitted to them). This means bias and politicisation aren’t eliminated, time-to-publish is longer than ideal, and costs are still significant.

The change in model has also made scientists weary of potential prestige losses in publishing there, and so fewer high impact papers now come out in eLife. Indeed, the journal has recently been stripped of its official impact factor altogether.

The best use-case for eLife now is if scientists wish to get the stamp of approval of peer review without being forced to do extra experiments (say, if the first author has moved to a different lab/career).

A hypothetical optimal publishing system would adopt the capability to edit published papers post-review from eLife.

OpenPsych

The field of psychology is particularly rife with publication bias, politicisation, and data that doesn’t replicate. OpenPsych takes a novel approach inspired by anonymous internet forums. Papers are uploaded (through the filter of an editor) and a sub-forum is created where reviewers, recruited by the editor, can openly discuss the paper with the authors (double-blinded). Authors can re-upload versions as they go.

This is nice because it is a much more streamlined continual process of peer review, and much more like an actual conversation than a judicial decree (which is what traditional peer review feels like). There is also zero cost of publishing because there are basically no running costs and OpenPsych relies heavily on volunteered time. Still, the prestige issue is not solved and editors retain power to inflict their bias if they wanted to. The forum-style of peer review has been instrumental for combatting accusations of pseudoscience in OpenPsych, which stem from the controversial nature of lots of the research there.2

A hypothetical optimal publishing system would adopt the forum-style transparent peer review of OpenPsych.

A novel solution

Ultimately, the various solutions thus far leave much to be desired. A perfect solution must be fast, free, allow scientists to accumulate prestige (to encourage adoption of the platform), have a filtering mechanism for high impact vs low impact papers, and allow for feedback from experts as a quality control mechanism.

The answer is already, literally, at hand: Substack.

Hear me out.

In part 1, I mentioned how Matt Ridley and Anton van de Merwe were unable to surpass the political filters of editors when trying to submit their scholarly review of the evidence for the origins of COVID-19. Ultimately, Matt published it on Substack. Let’s go through how doing so overcomes many of the issues of academic publishing.

Firstly, it is fast. You can publish on Substack whenever you want and it appears instantly. Further, the inbuilt word processor makes the uploading process even more seamless than preprint servers like bioRχiv.

Secondly, there is no bias or influence from editors or reviewers. Authors can publish what they want as they intended it to be. The politicisation of science and obsequiousness towards editors vanishes instantly.

Thirdly, open access is free. Authors can publish articles with no paywalls. If they want to implement a paywall, it hurts the impact of their research but at least the money goes to the actual scientists (with a small slice going to Substack of course). I would recommend that an academic version of Substack bans paid content altogether though—acting as a non-profit arm of regular Substack (more on that later).

Okay but how is this any different to a preprint server then? What about the prestige issue and peer review? The key difference between a preprint server and Substack Scholar (I’m coining that) is the leveraging of social media mechanisms.

Solving the prestige problem

When you go on Instagram, you aren’t faced with a random selection of all Instagram posts. Instead you are given an algorithmically curated selection of posts from people you manually follow and from accounts that are predicted to maximise your engagement (either negatively or positively). In 2025 we know to decry the social media algorithms as evil and manipulative. Yet the very same type of algorithm could help Substack replace conventional academic publishing. As things currently stand, Substack recommends articles for you to read. This will be no different on Substack Scholar, except all the articles will be academic in nature.

Integrating a recommendation algorithm to academic publishing solves the prestige issue too.

Academics are glorified content creators. Our job is to create content (written articles) that is interesting to other scientists (i.e., has high engagement). Social media, like academic publishing, runs on prestige (or “clout”). On Instagram, the metric for prestige is follower count or likes on a Reel. For academics its h-index and citations on a paper. Charli D’Amelio and Stephen Hawking are truly two peas in a pod, if you think about it.3

Previous attempts to fix academic publishing have tried to ignore or even reject the notion that academics are motivated by prestige. This is a fool’s errand. Why try to deny human nature when you can leverage human nature to create a better system?

Successful academics publishing on Substack Scholar will gain higher subscriber counts. This makes “high impact” an attribute of individual scientists or labs, and not journals (like some kind of cool kids’ club) that you can game your way into or be barred from for unfair reasons.

Beyond subscriber count, individual pieces of research will see the limelight they deserve thanks to algorithmic boosting. If some unknown researcher publishes something truly amazing, scientists *will* see it.

The prospect of gaining prestige via Substack is already an attractor for many academics who dabble in writing (Eric Topol, Steve Stewart-Williams, Erik Hoel, little old me, etc.). If a viable way of merging their regular Substack with Substack Scholar presented itself, I’m sure academics will eagerly take up the opportunity. And if prestige alone isn’t sufficient, academics can have a paywalled regular Substack to accompany their open access Substack Scholar, which they can use to communicate their work in plain English to the general public and garner some revenue.

The need to integrate social media with academic publishing is already apparent to big journals. Social media teams are employed at these journals to ensure maximum reach of their publications. Indeed, I recently published a paper as first author and was asked to make a YouTube Short to promote the paper! (it’s here since you asked—and yes I know I’m a terrible influencer). Preprints, too, rely on the same social media mechanisms for dissemination—either being posted about by the authors or by the automated bioRχiv account itself.

These days I find most science papers to read via my 𝕏 algorithm. Using a thread to explain a paper is now a crucial part of publishing. Indeed, one of the ways in which prestigious journals uphold their prestige nowadays is simply by having larger social media followings. There is no reason why social media accounts of individuals can’t functionally replace those of prestigious journals—in fact they regularly do on 𝕏.

If we published the primary research articles on the very same platform that we shared Notes and SciComm breakdowns of the primary research, the whole process would become seamlessly integrated and we wouldn’t have to deal with link suppression4. Of course, there is no reason why Substack has to take on the mantle here. 𝕏 could equally come out with “𝕏 Research” and try to do the same thing. Substack is already optimised for long-form content, though, its user base is already more intellectually inclined, and it seems to have a first-mover advantage too, as I will come on to.

And peer review?

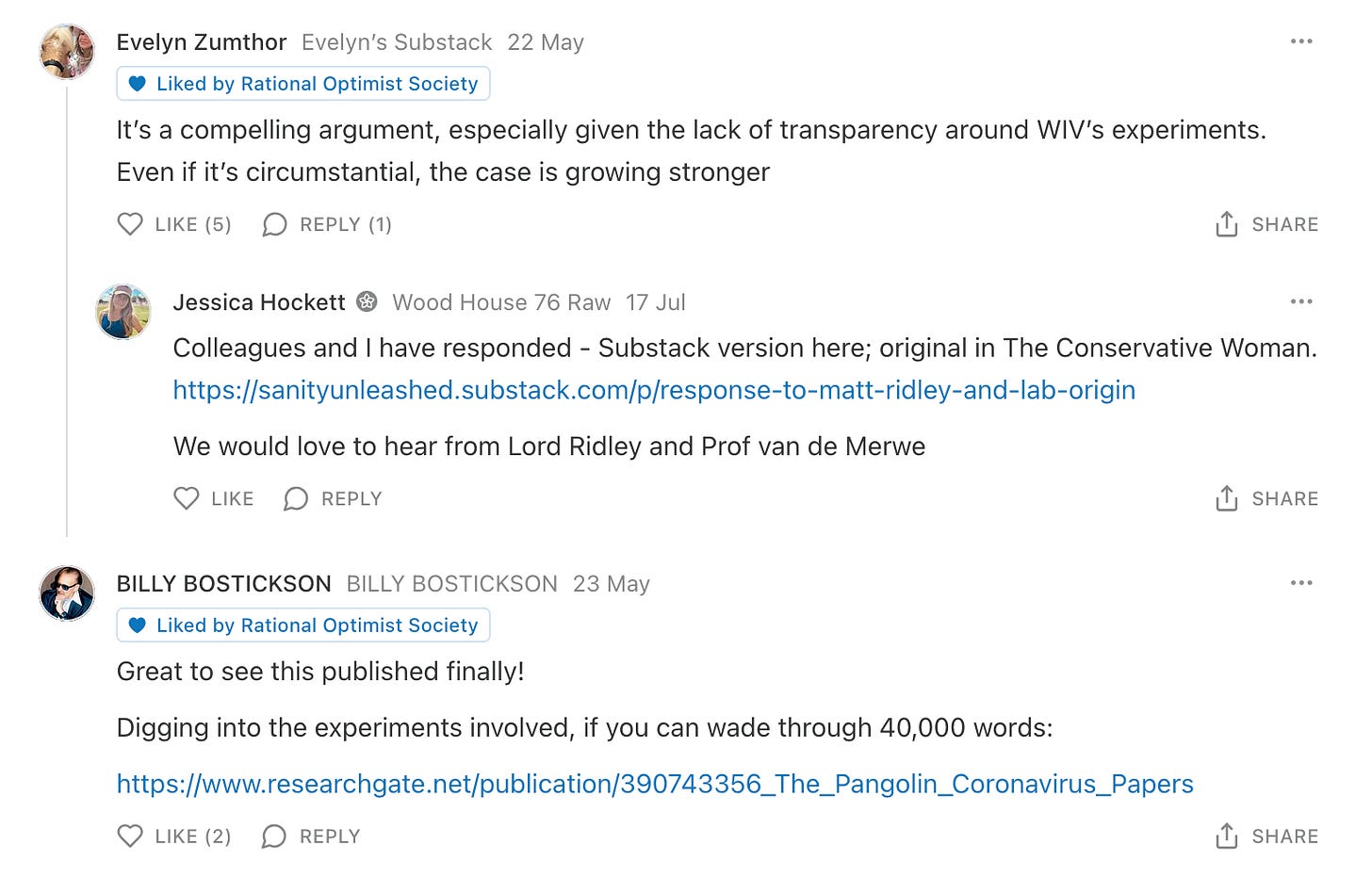

I’m glad you asked. If you go look at that article I mentioned on the origins of COVID-19 you’ll notice there are quite a few comments!

What you’ll find is (1) a little bit of bickering, (2) some very intelligent debate in good faith, and (3) some links to entire response articles offering the opposing perspective.

A comments section *is* peer review.

Instead of limiting review to a handful of scientists, every scientist will be capable of chiming in with their positive or negative reviews, or of quickly scribing response articles themselves. This also makes it much more likely that genuine experts can give their opinions on the article, instead of just the few scientists who the editor of a journal thought were appropriate experts with a free enough schedule.

What’s more, timely and salient comments on Substack posts often receive the most likes themselves, and so there is prestige/clout to be gained from engaging in this form of instant peer review. Algorithmic reward for peer review in the form of comments functions similarly to algorithmic reward for good articles in the first place. What’s more, like the review forums of OpenPsych, this format creates a much more conversational and therefore constructive environment.

Substack Scholar: an ideal publishing system

To make Substack Scholar work, there would need to be a few key implementations. Here are my specific recommendations:

Substack Scholar would need to be integrated with, but separate/parallel to regular Substack. I would recommend that only those with institutional emails, validated Google Scholar accounts, ORCiD, or some other measure of scholarliness are able to create Substack Scholar accounts (although excluding too many outsiders might be detrimental). This ensures research is traceable and legitimate (for example, preventing a wave of AI-generated slop from being pumped out by anonymous bad actors).

As I’ve already mentioned, I think insist that all Substack Scholar posts should be free and open access, subsidised by paid content on the regular Substack side of things if needed (although the running cost of Substack Scholar would be minimal anyways). The subsidy will pay for itself in the form of increased overall Substack traffic.

The comment section model of peer review works only if spam is filtered. Algorithmic boosting of the best comments solves this partially. Another simple solution is to have two parallel comment sections under Substack Scholar articles. Those with Substack Scholar accounts can comment in and view both sections, but non-scholars can only view the scholarly comments, not contribute to them (but they can contribute to the normal comment section of course).

Substack articles are currently editable. After publishing, an author can go back and fix typos as they please and it will just update without a trace. This should be changed for Substack Scholar. Amendments should still be possible, but version histories should be kept and made available for viewing always. It should be clear which version comments are referring to (perhaps just create separate fresh comments sections for new versions of articles). This means if authors are persuaded by the arguments of commenters, they can make changes as with regular peer review (or they can just publish a new article altogether).

The referencing/citation UI/UX can be enhanced. As things stand, I typically cite research by linking the article with an in-text hyperlink. Alternatively, I add a footnote and manually type out the citation. Substack Scholar would fix this friction, perhaps with EndNote or Mendeley plug-ins, or its own referencing software add-on. It is essential that researchers can easily cite other work, and also have their Substack Scholar articles themselves cited.

For this to happen, articles need a digital object identifier (DOI), like any other research article or preprint, with an accompanying PDF available for download. A DOI also allows for integration into funding and curation databases. Persuading funding bodies to accept Substack Scholar articles on researchers’ CVs as valid pieces of work is crucial. I recently submitted a bunch of applications for postdoctoral fellowships (mini grants that only cover my salary). All of them bar one allowed me to include bioRχiv preprints in my list of publications. This fact surely plays a large role in the widespread adoption of bioRχiv. There is no reason why Substack Scholar cannot follow suit.

Finally, the algorithm would need constant fine-tuning to ensure it serves scholars well. Whether people choose to get their research articles direct via subscriptions to their favourite scientists or by spending time on the Substack app or site will be up to them. Either way, Substack Scholar should aim to maximise productive scholarly debate and dissemination of high quality and interesting research.

The time is now

Substack Scholar genuinely could work, and I’m not the only one to think so. I was recently chatting with

, a product researcher at Substack, who has been eyeing up the ever-increasing number of academics who write on Substack. The idea of assigning DOIs to academic Substack articles is already in the pipeline. Doing so will enable the academic articles selected for the pilot to feature on Google Scholar, which will be a key first step. I hope that this trial goes well and that Substack considers the ideas I have put forth here.We are at a crucial point with regards to academic publishing. The COVID-19 pandemic and enhanced freedom of information in the social media era has put (scientific) institutions under intense scrutiny—few more so than academic journals.

In part 1, I mentioned how the NIH is instructing all NIH-funded research to be immediately available to the public via PMC. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, one of the largest private US funders of biomedical sciences, went one step further with their recent announcement proclaiming that they won’t allow their grants to be used for article processing charges at all, and instead insist that all HHMI-funded research is uploaded to bioRχiv from 2026 onwards. Clearly, the appetite for change is there.

It has been said that science progresses one funeral at a time—the idea being that dogmata only die out when the people who uphold them do so first. Fortunately, I think that the adoption of an incentive-laden superior publishing system that leverages the tech of social media will progress one birth at a time—the birth of research labs that is.

Once I run my own research lab—deo volente—the smart move will be to publish via Substack Scholar. The ideal early adopters of Substack Scholar will be end-of-career scientists who have huge personal prestige and nothing to lose by trying something new and postdocs like myself who can be convinced to switch systems ab initio when starting their own labs. Indeed, targeting the birth of new labs may be the best option given the prevalence of closed-mindedness among older academics.

With that in mind, we might expect adoption of Substack Scholar for publishing primary research to be a little slow off the mark. Rome > 24h etc. However, I imagine it will very quickly become the hub for secondary research. Publishing a scholarly review or perspective (which synthesises already-published data, rather than reporting data for the first time) entails much less risk for early adopters, and will likely play a key role in building the credibility of the publishing platform before primary research follows.

In the coming months I plan to write a scholarly commentary summarising what the research tells us about how much protein we should be eating for optimal health outcomes. There have been some strong claims both for and against high-protein diets, and I think a closer look at the evidence is sorely needed. I think I will save myself the the cost of APCs, the strife of dogmatic reviewers, the bias of ideological editors, and the frustration with slow turnaround and just publish it here instead.

The three big machine learning conferences, ICML, NeurIPS, and ICLR (the proceedings of which act in the same way that journals do for other sciences), have exploded in size in recent years— with 21,575 papers submitted to NeurIPS this year (up from 9,467 in 2020). Such immense volume is impossible to properly peer review, not least because there are so few very experienced ML researchers to properly review papers and so many young researchers pumping out research the whole time. At this point formal peer review in machine learning has basically crumbled, with the process being as good as a roll of the dice. Indeed, this year NeurIPS had to randomly reject ~400 papers that they had already accepted because the conference had become so oversubscribed.

I’d advise venturing onto the journal’s Wikipedia page with truck loads of sodium chloride

I deleted TikTok some time in 2020, so apologies if my reference to Charli D’Amelio is a bit Boomer.

𝕏 punishes posts that share links to external sites because it reduces time spent on the app. This is one of the reasons the app suffers from low quality of content in my view.

It's an interesting idea! I've been trying to think how this might work for chemistry research. There could be some technical issues to address about experimental data and how it is made available, but I'm sure that could be solved.

Chemistry has had more barriers to open science initiatives. Big traditional publishers are/were dominant. The primary ways to search the chemical literature were controlled by a few of those publishers. Prestige publishing determines your career opportunities. I've seen so many organic chemists who are obsessed with publishing in the big name journals even to their detriment. Better to let something go unpublished for a year if there's a chance, however small, of getting into JACS, for example. Oh, and the standard chemical drawing software is exorbitantly expensive now because its developer knows they can charge whatever they want. Things seem to be slowly changing, but there are some pretty conservative voices in the field. Even the American Chemical Society has open access journals in some form now.

"Persuading funding bodies to accept Substack Scholar articles on researchers’ CVs as valid pieces of work is crucial" - I'm curious if you have any thoughts about what it might take to achieve this.