The unmasking of academia's latent disdain for scientific progress

"it's actually just a grey wolf with a few gene edits" ☝️🤓

Time magazine recently published a cover story celebrating the immense achievement of Colossal Biosciences, who managed to bring back the dire wolf from extinction. Sort of.

What they really did was the following:

sequence the genomes from two ancient dire wolf specimens with unprecedented genome coverage

develop a novel non-invasive way of obtaining genetic material from living animals to create reference genomes for a wide range of related canids

map the phylogeny of the dire wolf, finding that the grey wolf is the extant species with which it shares the most genetic alleles

determine the function of proteins that are encoded by genes that differ slightly in sequence between dire wolves and grey wolves

shortlist a subset of these proteins that would give rise to crucial phenotypic traits that separate dire wolves and grey wolves, particularly with regard to their differing ecological niches

develop a novel multiplex gene editing technique to be able to edit many of the genes encoding these proteins in one go

make precise edits to the grey wolf genes on this shortlist to recreate the dire wolf gene sequences and thus reproduce dire wolf phenotypes from dire wolf genotypes

This is really really complicated and incredibly impressive science. Yet an alarmingly common response from the scientific community was to criticise: criticisms of the validity of the claim of “de-extinction”; criticisms of the usefulness of the endeavour (as if a majority of academics have ever done anything directly useful for humanity in their lives); criticisms of the savvy marketing of their discovery (I thought public engagement was a key component of what it means to be a scientist?). Compare and contrast the tone and narrative of this New York Times article with this Science news piece. The level of cynicism and contempt spilling out of the Science hit piece-cum-news article is exceeded only by its level of bias and sloppiness. Take this paragraph:

Others have argued that efforts to resurrect lost species divert resources and attention from threatened and endangered species living today. In a comment to the New Zealand Science Media Centre, University of Otago geneticist Nic Rawlence said if it were up to him, companies like Colossal would “develop de-extinction technology but use it to conserve what we have left.”

Yeah nice point except for the fact that leveraging their technologies to conserve and protect extant endangered species is literally exactly what Colossal Biosciences is already doing and what they’ve always said was the motivation for their work. A completely fake criticism that the writer for Science clearly did zero due diligence on. There are other outright falsehoods floating around too, including claims that Colossal chose the wrong starting species and that the black-backed jackal is actually evolutionarily closer to the dire wolf. I think these critics were perhaps thrown off by the order in which the species names appeared in the below figure from Colossal’s pre-print, ignoring what the phylogenetic tree actually shows. As I pointed out to one cynical X user, Colossal wrote the book on dire wolf phylogeny—obviously they wouldn’t deliberately make their job harder than it needs to be.

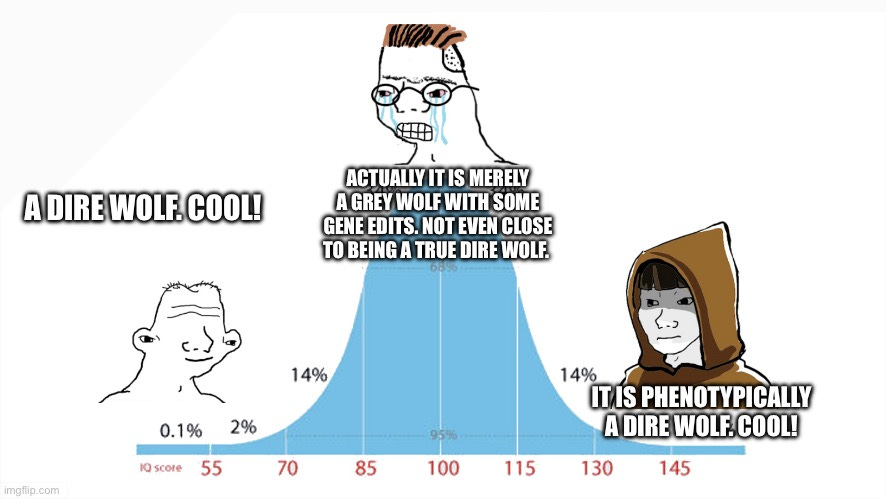

Many cynics are diving headfirst into pedantry as their primary method of attack—splitting hairs over calling the animals “dire wolves” and insist on minimising the achievement via pedantic and dogmatic (wolfmatic?) definitions of “species”. Yes, of course it’s true that these aren’t 100% genetically identical dire wolves, that the environment these wolves are placed in cannot completely replicate that of the Pleistocene, that they have no dire wolf parents to learn dire wolf behaviours from, that their diet will likely differ from that of Pleistocene dire wolves and this likely further diverges their microbiomes and physiology. To completely adjust for all of these differences would be nigh-impossible. Further, all of these parameters, both genetic and environmental, differ immensely between a Canadian dire wolf in 100,000 BC and a Peruvian dire wolf in 15,000 BC, so which is the “true” dire wolf?

The most valid criticism is the point that these are not 100% genetically pure dire wolves—something that nobody is claiming, least of all Colossal. Might it be possible in the future to completely reconstruct the entire dire wolf genome and create a 21st Century dire wolf that is genetically identical to a Pleistocene dire wolf? Perhaps. What would be the point, though? The critics seem to miss the motivation for why Colossal are doing what they are doing. They are first and foremost a conservation company. They are unique because they develop and leverage synthetic biology to achieve their conservation aims, with hugely beneficial side-effects for fundamental biological research and medical research alike.

In light of this conservationist bent, the species definition that Colossal cares about the most is based on ecological niche. After all, a vacuum in ecological niche is arguably the most impactful negative consequence of species extinction. It’s perfectly valid to define a species by its ecological niche. It’s also valid to define a species by geographical location, genomic sequence, morphological features, or ability to produce fertile offspring with other individuals within the group. All species definitions are somewhat arbitrary human-drawn lines in the sand of the continuous process of evolution, and are therefore mutable. Even if Colossal’s chosen definition of a species is an uncommon one in the post-genomic revolution era, it isn’t “wrong” by any objective measure.

Given the tentative validity of many of the criticisms levied at Colossal, we must ask why some academics have reacted this way. Unnecessary criticism and excessive cynicism serve two main functions: (1) to keep others down, and (2) to inflate one’s own ego. Criticising feels really good. It’s a display to others that you are incredibly smart and have intelligently dissected problems that others did not see on account of your relative talent and knowledge and their relative ignorance. Nowhere does this social dynamic play out more strongly than in academic science. There are structural incentives that create this tendency, as well as a selection effect for people with this bias to become academic scientists in the first place that I will explore in a future essay perhaps.

When failing to be able to pinpoint any specific flaws in the recent pre-print on the dire wolf phylogeny, authored by Colossal’s team, some simply assert, “It’s probably full of errors. I won’t take it seriously until it’s been peer-reviewed.” Peer review is the motte that academics always retreat to when their own attempts at interrogation are insubstantial. We are assured that this mythical process ensures only the most rigorous and best science gets published. Except that’s flagrantly untrue. Loads of totally unreproducible (read: useless) science gets through peer review. If peer review was actually rigorous, it would have caught the blatant data manipulation and fraud published in Nature that led the Alzheimer’s field on a wild goose chase for decades, for example. Peer review has its place, but it is the jewel of credentialism and the ultimate appeal to authority. I have much more to say against peer review. Again—perhaps another time (I say this as if Michael Eisen has left any stones unturned).

Now, to be fair, I don’t know what I don’t know. There could be methodological flaws that I didn’t pick up in my reading of Colossal’s pre-print. Maybe peer review will give them a hard time, but I’m pretty positive it will get published in a top tier journal eventually. To be honest, though, this is irrelevant. Publications are a side quest for Colossal. The great thing about this dire wolf breakthrough is that it is real. The wolves exist. It is a concrete achievement. Publishing a highfalutin Cell paper is great, but doing so rarely brings the metaphorical rubber any closer to the metaphorical road. In two years time when a fully-grown pair of adult male de-extincted dire wolves are stood side-by-side with a grey wolf, peer review or lack thereof becomes completely irrelevant.

I sometimes lament the fact that the endpoint of what I do as an academic scientist is getting a journal article published (or is the ultimate goal to use these publications to get more money? I can never tell). If you’ve learned to frame scientific success through the lens of credentialism, it must hit a nerve that George R. R. Martin and some tech bros without so much as an undergrad degree in biology are authors on a paper that is more impactful than what most of us academics will ever produce in our lifetimes. Creating real progress in the way that Colossal is doing dwarfs the triviality of words on paper (or, more accurately, paywalled PDFs), and some academics hate this fact.

It is no secret that academic scientists are overwhelmingly of a progressive persuasion. Yet the dire wolf saga has revealed this progressivism to be in name only. These “progressives” are in fact conservatives with respect to the authority and dominance of their ivory towers, and their conservatism overpowers any progressivism that they would otherwise exhibit with respect to science, technology, or ecology. There is a bitter irony in how the pearl-clutching conservatism of “progressive” academics is being unmasked by technologically progressive conservationists. This disdain being shown for genuine scientific progress by some academic scientists and adjacent liberal elites is a tragic indictment of academia and the “progressive” establishment.

This piece depressingly misunderstands what science is. What they did is a cool marketing trick and a decent (g)engineering application, but it doesn't seem to much advance science's actual goal of amassing useful, explanatory knowledge. This reminds me of those braindead takes "Large Language Models make linguistics useless". No, LLMs are themselves useless for what theoretical linguistics does, they're an NLP tool. Or, to take a natural science example, it's people more impressed with physics tricks known for decades or even centuries than with the blink-and-you'll-miss-it discoveries of late.